Intense Exercise and Mortality Risk: Why Intensity May Matter More Than Duration

In a groundbreaking study published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, researchers have presented compelling evidence suggesting that intense exercise and mortality risk are more closely linked than previously understood. While both exercise intensity and volume are significantly correlated with reduced all-cause mortality, intensity appears to play the more critical role, particularly in relation to cardiovascular health.

Rethinking Exercise Duration: Every Minute Counts

Historically, the standard advice for exercise focused on duration. It was commonly believed that physical activity must occur in sustained bouts, typically of at least 10 minutes, to yield measurable health benefits. However, the World Health Organization has shifted its guidance, asserting that “every minute counts,” regardless of the duration of each exercise session.

This updated perspective stems from studies examining the benefits of shorter, fragmented activity intervals. Yet, while interval length has received attention, fewer studies have directly compared the broader categories of exercise intensity and total daily volume, until now.

Intensity Versus Volume: What the Data Show

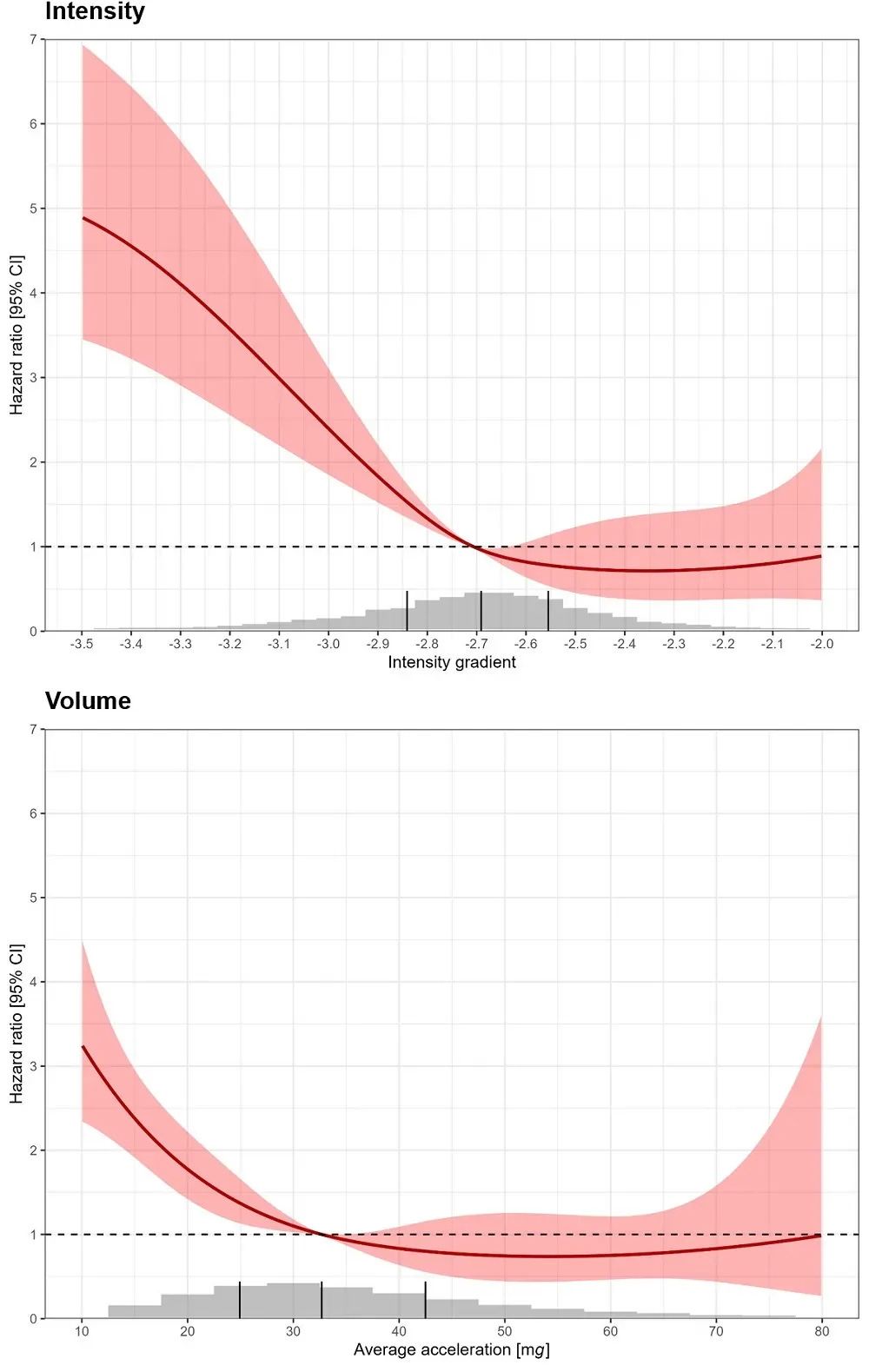

The researchers utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which includes a representative sample of U.S. adults. The study cohort had a mean age of 48 and an average BMI of 28. Participants wore wrist accelerometers for seven days, allowing researchers to quantify their total movement volume (measured as average acceleration, or AvAcc) and the intensity gradient (IG), which compares the most intense activity to the least.

Findings showed that while both volume and intensity were linked to a lower risk of death, intensity had a stronger and more consistent association. Specifically, individuals who performed less intense exercise, especially below the average activity level of a 70-year-old, faced a higher risk of mortality. Conversely, more consistent and intense activity was correlated with longevity.

The Cardiovascular Connection

The data also revealed that intensity had a stronger correlation with reduced cardiovascular mortality than total activity volume. While AvAcc fell just short of statistical significance for cardiovascular outcomes, IG demonstrated a robust inverse relationship, mirroring patterns observed in all-cause mortality data.

Why Fragmented Exercise Might Be Less Effective

Not all physical activity patterns yield the same benefits. The study highlighted that fragmentation, sporadic bursts of activity, was associated with higher mortality risk. For instance, someone who briskly walks at several random intervals for a cumulative 15 minutes would benefit far more by consolidating that activity into one continuous 15-minute walk. Consistent, uninterrupted activity bouts of 5, 15, or 60 minutes were linked to a lower risk of death.

Therefore, even though “every minute counts,” scheduled, continuous bouts of relatively intense exercise may offer superior protective benefits compared to fragmented movement.

The Age Factor: Decline in Intensity with Age

The researchers accounted for chronological age when analyzing hazard ratios. Predictably, older individuals, especially those in their 80s and 90s, tended to move less and with lower intensity. This decline was consistent across both genders. Importantly, the data suggest that the drop in intensity with age may have a stronger impact on health than the drop in total volume.

Study Limitations and Corroborating Evidence

The study did present several limitations. It lacked data on smoking status, alcohol consumption, and mobility impairments, which could affect exercise patterns. Furthermore, reverse causation remains a concern; individuals who engage in less-intense activity may already have undiagnosed health issues. To minimize this, the study excluded deaths occurring within 12 months of data collection.

Despite these limitations, the findings align with prior research, including UK Biobank studies showing that high-intensity activity is vital for preserving health and resisting age-related decline. The results also support existing evidence indicating that cardiovascular and respiratory fitness depend heavily on exercises that are intense and sustained enough to challenge the body’s systems.

Your Call to Action for Intense Exercise and Mortality Risk

This new research makes it clear: intensity matters. For those seeking to reduce their mortality risk and support cardiovascular health, simply moving throughout the day may not be enough. What truly counts is engaging in regular, uninterrupted sessions of moderately intense to vigorous activity, whether that’s a brisk 15-minute walk, cycling, or structured exercise.

To implement this into your lifestyle, start by identifying opportunities for continuous, intentional movement. Schedule 15 to 30-minute windows in your day for focused activity. Aim to raise your heart rate and sustain that effort. Whether you're walking, jogging, swimming, or dancing, consistency and intensity will pay long-term dividends in health and longevity.

Now is the time to turn movement into a habit, not just a metric.

My YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/@MyLongevityExperiment

Study Links:

Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., … & Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British journal of sports medicine, 54(24), 1451-1462.

Jakicic, J. M., Kraus, W. E., Powell, K. E., Campbell, W. W., Janz, K. F., Troiano, R. P., … & 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2019). Association between bout duration of physical activity and health: systematic review. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 51(6), 1213.

Rowlands, A., Davies, M., Dempsey, P., Edwardson, C., Razieh, C., & Yates, T. (2021). Wrist-worn accelerometers: recommending~ 1.0 mg as the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in daily average acceleration for inactive adults. British journal of sports medicine, 55(14), 814-815.

Rowlands, A. V., Edwardson, C. L., Dawkins, N. P., Maylor, B. D., Metcalf, K. M., & Janz, K. F. (2020). Physical activity for bone health: how much and/or how hard?. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 52(11), 2331-2341.

National Center for Health Statistics (US). (2013). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2007-2010. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service.

Dempsey, P. C., Musicha, C., Rowlands, A. V., Davies, M., Khunti, K., Razieh, C., … & Samani, N. J. (2022). Investigation of a UK biobank cohort reveals causal associations of self-reported walking pace with telomere length. Communications Biology, 5(1), 381.

Hov, H., Wang, E., Lim, Y. R., Trane, G., Hemmingsen, M., Hoff, J., & Helgerud, J. (2023). Aerobic high‐intensity intervals are superior to improve V̇O2max compared with sprint intervals in well‐trained men. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 33(2), 146-159.